History of Bethesda, Maryland

Table of Contents

- From Ice Age to European Arrival: 16000 BC-1600 AD

- A Frontier in the Province of Maryland: 1600-1700

- Independence on Exhausted Land: 1776-1861

- A Divided Town in a Divided State: 1861-1865

- Suburban Growth by Rail, Trolley: 1865-1896

- The Foundation for Growth: 1896-1920

- Boom Without Bust: 1920-1932

- Research & Revolution: The NIH and Bethesda, 1932-1942

- Modern Bethesda: 1942-Present

Around 16,000 BC, as the last ice age began its retreat, temperate weather slowly returned to the Mid-Atlantic. By 9500 BC, Paleo-Indians inhabited the Chesapeake Bay region. Generations of these Paleo-Indians witnessed the gradual formation of hardwood forests and coastal wetlands, subsisting primarily on local nuts and fish. Evidence of these hunter-gatherers survives in the Clovis points that archaeologists have found and identified.

As centuries passed, the melting ice flooded area rivers and the Chesapeake Bay gradually took shape. Yet it was not until 2,000 years ago that the bay settled on its present form. Around that same time – and continuing for 1,000 years after – indigenous communities shifted from dependence on bow-and-arrow hunting to more sedentary, agricultural societies. There are traces of permanent settlements in Glen Echo and Cabin John, although the largest indigenous communities were in Georgetown and Anacostia.

Established, growing populations fostered development of complex trade networks, but they also increased competition for land and resources. This competition, in some instances, led to conflict. Algonquin speakers, for whom many area rivers are named – including the Potomac – were the dominant local culture.

By the time of European arrival, war and disease had already diminished indigenous communities and many of these prominent settlements had been abandoned.

Englishman John Smith mapped the Chesapeake region in 1608, but fur trader Henry Fleet was the first European to venture into the area that would later become Bethesda. Fleet sailed up the Potomac River four miles past Georgetown. There, he encountered the Piscataways, who had formed a loose confederacy of villages along the eastern shore of the river.

For two years, Fleet was either a guest or prisoner of the Piscataways – the historical record is unclear – but his time in the area secured his position as a trusted source of information on Maryland. After he returned to England, Fleet published accounts of fur-rich tribes and the prospect of gold, which grew interest and financed his return to Maryland, where he served as translator and guide for early colonists. He later won proprietary rights to 2,000 acres and became a member of Maryland’s colonial legislature.

Growth in the Province of Maryland led to the formation of local government via counties. Boundaries tracked along land patents issued by the Calvert family, which had won the right to form the colony through a charter granted by King Charles I of England in 1634.

Most early Maryland landowners were absentee landlords who had little interest in living on or improving their territories. A tax on land holdings, known as the quitrent, was collected regardless of the land’s productivity. This made land ownership expensive and dissuaded settlement in Maryland; other colonies taxed land relative to production.

For most land owners, the financial solution for maintaining their holdings was tenant farmers. Scottish, English, and Welsh farmers – both free and indentured servants – were the first Europeans to till the Maryland soil. Later, Germans, Swiss and Dutch colonists from Pennsylvania moved south into the Montgomery County region. While most tenant farmers worked small plots with their families, larger farms depended on African slave labor.

Rural tobacco farming defined Bethesda throughout the 1700s. As conflict between the American colonies and England grew, Maryland – aware of its dependence on tobacco exports – was tentative. The First Maryland Convention in June of 1774 agreed to suspend imports but to stop exports only if other colonies approved similar plans. The war for independence spared Maryland soil from battle, though the bay area saw naval action, and Maryland supplied and equipped American soldiers fighting on other fronts.

Bethesda, comprised of roughly two dozen families in 1776, officially became part of Montgomery County on September 6 of that year, when Frederick County was divided into three parts. The other component of the triumvirate, Washington County, reflected the patriotic mood – General Richmond Montgomery and General George Washington inspired both names.

American independence affected Bethesda and Montgomery County in unexpected ways. The Confiscation Act of 1780 redistributed many area lands, as Loyalists and European merchants unwilling to pledge allegiance to the fledgling nation saw their properties auctioned in 1782. At that time, Robert Peter was the wealthiest resident in the Georgetown area, with some 20,000 acres of property, including a number of Bethesda farms. Only five other landowners held at least 3,000 acres.

The creation of Washington DC in 1790 had a greater impact on the region, even if the event went largely unnoticed on small farms in Bethesda. The Residence Act of 1790 extracted 64 square miles of land from Montgomery and Prince George counties, including Montgomery County’s principal city of Georgetown and the valuable tax revenue of several large farms.

Skirmishes led by Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early against Union forces on the Washington and Rockville Turnpike caused brief panic in July 1864, with some Bethesda residents burying valuables and running away in anticipation of a full-scale attack. A one-day engagement took place at the Old Stone Tavern in Bethesda, dismissed as a raid by Union authorities but later, and more dramatically, recounted as the Battle of Bethesda.

On November 1, 1864, Maryland abolished slavery, though the fate of the Peculiar Institution was in no doubt by then – Congress passed the 13th Amendment in January 1865. For newly freed blacks, abolition failed to address the persistent social, economic and political equality.

Civil War hostilities officially came to a close on April 8, a week before Lincoln’s assassination. Despite 620,000 Civil War deaths and the abolition of slavery, the Bethesda area, having purged itself of reliance on tobacco decades before and with only a scant population, quickly returned to its antebellum life as a quiet, rural town. It took two more transportation revolutions to transform Bethesda.

William Darcy managed one of the few commercial establishments in the area, known simply as “Darcy’s Store.” Darcy also served as postmaster and the quiet crossroads along the turnpike between Georgetown and Frederick had been known simply as Darcy’s Store.

On January 23, 1871, Robert Franck took over postmaster responsibilities and relocated the post office. The Presbyterian Bethesda Meeting House, located just up the pike, had taken its name from the biblical Pool of Bethesda, noted for its tremendous healing powers. Franck truncated the name to Bethesda, winning the anecdote a foundational place in town history. Seven years later, Montgomery County Commissioners established the Bethesda Election District, District 7, which covered some 35 square miles.

A few years before, at the close of the Civil War, the metropolitan branch of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad won approval for its charter and its northwest-southeast rail line came into service in 1873, cutting diagonally across Montgomery County. The train offered the first realistic opportunity for suburban development in the county by making it possible for Washington D.C. residents to become commuters and enjoy the fresh air of the country and for Montgomery County residents to seek employment beyond farm life in the city. By 1880, two dozen trains rolled through each day.

The earliest suburban growth concentrated closely to the rail lines and Bethesda was not on the list of stops. As a result, the real estate boom neglected Bethesda. Moreover, the rail line lowered dependence on the turnpike, in effect, diminishing Bethesda’s importance within the county.

Alta Vista, the first true Bethesda neighborhood, appeared in the 1880s, but Bethesda was still primarily a collection of small farms with a couple of country stores, blacksmiths and other tradesmen, a tavern and the trappings of an agricultural community – windmills, barns and the like. Then, in 1891, Bethesda earned its spot on the Montgomery County map. The trolley arrived.

Suburban development in adjacent areas like Chevy Chase, a hamlet carved especially for the elite of Washington D.C., accelerated. Yet development restrictions in places like Chevy Chase, which forbade commercial development, would later work in Bethesda’s favor. And nothing could match the impact of the personal automobile, which finally untethered suburban development from fixed rail lines and ignited decades of exponential growth in Bethesda.

The Civil Service Act of 1883 provided a stable population of federal employees and secured a consumer base for the suburbs sprouting throughout Montgomery County. In November 1880, the county adopted prohibition, which stayed in place until the national repeal five decades later. The first post-bellum school in Bethesda opened in 1894; a school for blacks had opened in 1880. (A special levy on the few black landowners ensured no local, white tax dollars funded it.)

These developments hinted at coming progress, though the centrality of rail to suburban development still limited growth in Bethesda. In the final decades of the 1800s and into the first decade of the 1900s, the strong correlation between population and proximity to rail highlighted the connection. Without abundant local industry, the opportunities to make a living in Bethesda were farming, meeting local demand for building trades or commuting to the capital.

Bethesda finally got its railroad in 1910, an 11-mile stretch of the B&O, but the rail line served freight traffic exclusively, a “coal and construction” railroad. The railroad nursed a small quarrying and stone-cutting industry but never attained transformative influence. For many residents, it was simply a blight on their bucolic landscape.

That same year, the Bethesda Central Switchboard came online, leading to a vast increase in telephone service. Before the switchboard, the only telephone – located in Darcy’s Store – offered the caller an opportunity to have a message passed to William Darcy, who would then relay it to the next passerby headed in the direction of its intended recipient. There were 1,000 telephones in Bethesda by 1920.

The personal automobile finally liberated Montgomery County from the constraints of rail and trolley lines. For Bethesda, this meant not just the possibility of development but also development with foreknowledge of the automobile and its impact. Unlike earlier suburbs, Bethesda would grow with the benefits of the motorcar at the forefront of developer minds.

Maryland’s foresight to build a network of highways – the state constructed more than 1,300 miles of roads between 1910 and 1915 to connect Baltimore and all county seats – accelerated the impact of the automobile. From 1910 to 1920, Bethesda’s population jumped from 3,217 to 4,757, with farming communities gradually extinguished in the southern-most parts of the county, though farming remained the primary use of land and employment countywide.

By the mid-1920s, just three decades after the trolley brought the town its first taste of stardom, Bethesda had become the center of suburban development in Montgomery County. While the count of buildings in 1926 included only one bank, three garages, five coal yards, two feed stores, two barbers, three lunchrooms, a grocery, drugstore, hardware store, and a fourteen-classroom schoolhouse, a full 40% of the 647 building permits issued that year were in Bethesda.

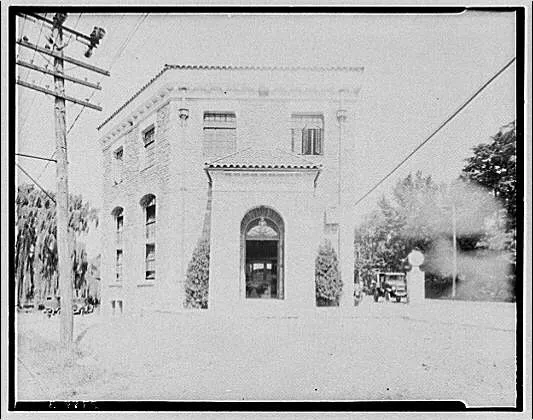

The Bethesda Chamber of Commerce, formed in 1925 with Tuckerman as its first president, saw the need for additional services, especially fire and police departments. Tightly spaced neighborhoods represented a catastrophic fire threat unlike the sparse, rural community of decades past. Firehouse No. 6, the first in Bethesda, was dedicated on December 16, 1926. For their part, police had seen a vast increase in need not simply from the added population but also from the burden of enforcing traffic laws and prohibition. A formal police force replaced rural constables that same decade.

Development and added services created an acute need for funding. E. Brooke Lee, who had spearheaded the push for the creation of the WSSC, proposed that the Bethesda Election District become a special taxing area. In addition to funding fire and police services, the revenue would support a better school system (through the late 1800s, education, especially in rural Montgomery County, was considered primarily a private responsibility), manage public parks, zoning and waste management.

The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (M-NCPPC) was also created in 1927. It expanded the existing powers of local government with the authority to tax and issue bonds to support purchase of park land. The M-NCPPC also developed master zoning and subdivision plans to supplement existing development regulations. A reassessment of Montgomery County in 1928 showed that of the $70 million of total property value, $30 million was located in Bethesda.

In 1932 a group of Bethesda farm women came together to sell products in a vacant Bethesda store. Christened the Montgomery Farm Women’s Cooperative Market, it was an immediate success and soon had more than forty members as well as capital stock, a board of directors and a paid manager. More than 80 year later, it is still in operation.

As an expanding suburb, Bethesda was nearing the limits of its geography. While the personal automobile had dramatically restructured the town, a land donation by a wealthy Bethesda couple soon changed the course of local history again. It also served as the catalyst for Bethesda’s modern reputation as one of the wealthiest, most educated places in the United States.

Suburban growth always looks inward, toward the metropolis that sustains it. While suburban residents may seek to escape the urban din, they remain dependent on the city center for employment, if nothing else. The same was true for Bethesda in the early twentieth century. Whether long-time residents traveled into the capital for work, or long-time capital dwellers moved out to the “country,” Washington D.C. remained the axis.

Luke and Helen Wilson, prominent Bethesda residents, had straddled the divide. Both came from wealthy families. Luke was the son of a clothing importer and made frequent trips across the Atlantic to manage the business. In addition to helping maintain and grow his wealth, his travels honed his interest in international relations, particularly after World War I.

In their later years, the Wilsons began considering their legacy and looked for ways to donate their 90-acre Bethesda estate, Tree Tops, to cement it. Their initial thought was to establish an international center that might improve international relations and avoid future conflicts. But the idea had poor timing: They began the search for supporters in 1930, just after the Great Depression had taken hold. This, and other ideas, failed to attract collaborators.

Exasperated, they wrote to President Roosevelt in 1934 to announce their intention to donate the land to the federal government. That letter, circulated throughout the administration, did find an interested suitor – the National Institute of Health.

The National Institute of Health traced its origins to 1887 and a one-room laboratory that studied and monitored immigrant diseases at the Marine Hospital in Staten Island, New York. In 1891 the facility, renamed the Hygienic Laboratory, moved to Washington D.C. There, it won authorization for the construction of a single building, but its mandate continued to outstrip its facilities, with an ever-expanding list of responsibilities that included regulation of vaccine production as well as research on various diseases.

The Social Security Act of 1935 expanded health funding, opening new possibilities for the Wilson’s land and the NIH. Surgeon General Thomas Parran, with the additional $2 million in funding from the Social Security Act in mind, decided to move the entire NIH facility to Tree Tops. The $100,000 animal farm was now a $1.46 million project. The creation of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1937, which received sponsorship from all 96 U.S. Senators, added to the NIH expansion in Bethesda.

Luke Wilson died in 1937, and Helen gave another 25 acres of the Tree Tops estate to support NIH construction. Construction on Building 1 began on January 11, 1938. By December of that year, it was operational. The remaining buildings were completed by June 1940, an achievement punctuated by a dedication from President Roosevelt in October. The NCI was the final building, Building 6, of the initial construction.

In addition to the NIH, the National Naval Medical Center also moved from Washington D.C. to Bethesda, beating out more than 80 other sites. (President Roosevelt is believed to have personally preferred and chosen Bethesda.) It was completed in 1942.

Almost overnight, Bethesda was home to hundreds of new jobs – the NIH employed 1,137 people by 1940 – many of which could be filled only by exceptional, highly trained doctors and scientists. Contrary to public fears, the neighborhoods surrounding the NIH campus soon became some of the most popular in Bethesda. And it was just the beginning.

Coinciding with the construction of the NIH was the publication of Bethesda’s first newspaper, the Bethesda Chevy-Chase Tribune, in 1937. It was later supplemented by the weekly Bethesda Journal. A public library opened in 1940, reflecting the growth of intellectual culture as well as the dramatic rise in population, which had increased some 700% since 1920. Between 1930 and 1940 alone, Bethesda’s population grew from 12,018 to 26,114; nationwide population growth averaged just 7% during that same period.

World War II claimed the lives of 316 Montgomery County residents. It also expanded the National Naval Medical Center, which went from an initial 1,200 beds to nearly 2,500 by 1945 to manage the burdens of war. Local Bethesda businesses started a “Buy in Bethesda” campaign, ostensibly to save gasoline and tire wear by supporting local retailers. Despite national policies of rationing and general shortages of some goods, building in Bethesda continued during the early 1940s.

After the war, Montgomery County welcomed home its soldiers. As they reintegrated into the civilian world, the need for post-secondary education became apparent, in part because the GI Bill offered college tuition to members of the military. In 1946 the county established Montgomery Junior College, the first junior college in Maryland.

Two years later, in 1948, Montgomery County became the first county in Maryland to adopt a home rule charter. The change in local government structure resulted from a Brookings Institution report in 1939 that indicted county commissioners for general poor governance, an official finding that many county residents had lamented for years.

Importantly, economic progress was not limited by federal expenditure. Private, high-tech industries followed federal researchers to Bethesda, creating a cluster of jobs on the cutting edge of science and technology. These jobs paid well and required high levels of education. And they are the jobs that continue to define modern Bethesda.

Though apartment construction faced stiff opposition in Bethesda, the area could experience only so much growth before the only option was up. Between 1940 and 1960, high-rise apartment construction increased from just 10% to 30% of all housing units, led by the Pooks Hill development. More homes also meant more schools: The county built 50 grade schools during 1955-65. Similarly, the population boom brought in major retailers, shopping centers and one of nation’s largest malls.

By the 1960s, about 40 years after the population boom began, Bethesda was not just bigger – it was more prestigious. That reputation, accelerated by the presence of the NIH, kept growing. In 1964, construction completed for the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495), a loop around Washington D.C. that enclosed Bethesda. “The Big Split” of Interstate 270 from the Beltway occurred just northwest of Bethesda, establishing a key transportation junction that fueled further growth of the high-tech corridor.

An unexpected shift in the division between up-county and down-county began to take hold. Down-county residents, including Bethesdans, historically had favored development, in contrast to up-county residents committed to a more rural, agricultural existence. But down-county residents, concerned about the seemingly endless growth of Bethesda, advocated a slow down to the suburban sprawl, while up-county residents noticed that further development might soon make their farms worth millions more than the crops they produced.

A final transportation revolution, the Metro train system, spurred another round of growth, especially for downtown Bethesda. Metro trains began running in the capital by March 1976, but the Red Line didn’t reach Bethesda until 1984. In the interim, Montgomery County adopted a master plan to concentrate pending development around the Metro station. A pyramid development plan allotted space for high rises at the Metro station, with progressively tighter height restrictions for projects as they moved away from the station. Public spaces such as parks were designed to provide a buffer between development types.

The Metro line stimulated growth in downtown Bethesda. Though suburban expansion had filled in down-county farmlands for decades, the downtown area looked similar from the 1930s through the 1970s. Soon, however, that antiquated vision faded, with large, modern office buildings taking the place of low storefronts. The area around the Metro became the Bethesda Central Business District, which included not just offices but restaurants, theaters and shopping outlets – more than 200 of them.

By the 1990s, a remarkable transition had taken place. Bethesda, once a bedroom community for capital employees, was home to three-quarters its residents’ jobs. The Interstate 270 corridor housed operations of more than 500 major companies by 2000, and the next generation of physicians and scientists were being trained at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, which graduated its first class in 1980. Bethesda was no longer a satellite of Washington D.C.; it had attained economic and cultural independence.

Into the 2010s, Bethesda, the latest bloomer among Montgomery County suburbs, moved to the forefront of a nationwide trend – residents looking for a blend of suburban tranquility and walkable access to exceptional shopping and dining. This “new luxury,” epitomized by districts such as Bethesda Row, drew lifestyle comparisons to Aspen, Colorado, from the Washington Post, which positioned Bethesda as “one of the most upscale suburban downtowns in the United States.” Forbes named Bethesda America’s second “most livable” city in 2009 and the “most educated small town” in 2014. CNNMoney honored it as America’s top-earning town in 2012.

For its part, the NIH continued to attract highly educated individuals – and churn out world-changing research. The Wilsons achieved their legacy: There have been eighty Nobel prizes awarded for NIH-supported research, including five to intramural NIH investigators, with achievements as grand as the deciphering of the human genetic code.

Bethesda, a census-designated place defined only by its geographic center, has no physical boundaries. Whatever imagined boundaries existed in the minds of its earliest settlers – or even those ambitious drivers of change during the early twentieth century – continue to be surpassed.

The rich history of Bethesda, Maryland plays a significant part in the independent living community at Fox Hill. Experience the beauty, culture and attractions of Bethesda when you join the senior living community.